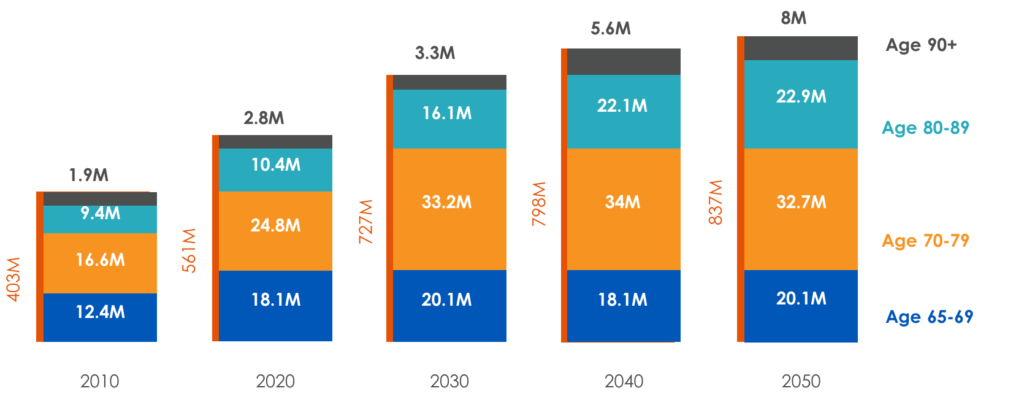

In 2030, more than one-fifth of the U.S. population will be more than 65-years-old, the traditional “retirement age.” Even if you are not among that Census Bureau-projected number, you surely care about — and maybe care for — someone who is. In either case, the main trend in health care news, realities and prognostications over the past decade has likely prompted concern.

Clinician shortages. Soaring costs. A devastating global pandemic. Where is this all leading?

The sobering figures, which we’ll touch on momentarily, may be only predictions, but they represent a clarion call to action. Preparation, adaptation and innovation are not luxuries. As the past three years have amply demonstrated, circumstances can shift abruptly and with relentless force. Fortunately, our individual and collective well-being is influenced not only by the crisis but also by our response.

In late 2019, just months before the coronavirus created unbridled chaos in the health care industry, this blog made a few predictions. Now, aided by more than two years’ worth of hard-earned insights, we’d like to revisit those — and speculate a little about what lies around the corner — from the perspective of an American senior.

The growing physician (and nursing) shortage

As the general population ages, so does the physician workforce. By 2030, an estimated one-third of physicians will be 65 or older. In a field already marked by high rates of burnout, the stress induced by COVID-19 has led many physicians to consider early retirement or at least a substantial workload reduction, according to a recent article on the American Medical Association (AMA) website.

Meanwhile, demand for health care continues to grow, with a larger insured population resulting from the Affordable Care Act (ACA) contributing to the rapid rise, according to a report in Human Resources for Health.

The anticipated physician shortage comprises both primary and specialty care practitioners, including geriatricians, whose essential skills include medication management and the recognition of asymptomatic and atypical presentations, the Journal of Aging and Health reports.

What does all this mean for seniors?

“Experience tells us that older adult patients demand sharply higher levels of care due to greater incidence of chronic disease, which will likely place much greater demand for physician services on a smaller pool of available physicians,” AMA President Gerald E. Harmon, MD, cautioned in a March 2022 column.

The shortfall extends to nurses and nursing assistants, many of whom also are nearing retirement age. These roles are very important to care settings outside the hospital, such as home health, nursing homes and hospices, as an article on The Doctor Weighs In website points out.

Successfully confronting the shortage will require focused effort on multiple fronts:

- More doctors. The Human Resources for Health report points to measures that could bring relief, including increasing numbers of medical school graduates and attracting foreign-trained doctors. In addition, the bipartisan Resident Physician Shortage Reduction Act of 2021 would gradually provide 14,000 new Medicare-supported graduate medical education (GME) positions.

- More assistance. An influx of advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs) and physician assistants (PAs) could help ease the burden. “(W)e project the supply of these providers will more than double over the next 15 years,” says a June 2021 report prepared for the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC). That growth exceeds the projected growth in demand for their services, the AAMC says, creating new opportunities for these clinicians to alleviate the load.

- Expanded use of technology. The use of telehealth and other technologies grew exponentially during the widespread pandemic shutdowns, proving that asynchronous and virtual care could be effective and efficient in optimizing limited resources.

The total cost of care continues to increase for seniors

U.S. spending on health care reached $4.1 trillion in 2020, nearly 20% of the nation’s gross domestic product, according to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). That’s more than $12,500 a person.

The nonpartisan Peter G. Petersen Foundation attributes skyrocketing spending to two primary factors: the aging population and the cost of medical services. The acquisition of new technologies, administrative waste in the insurance and provider payment systems resulting from the U.S. health care system’s complexities, and a lack of competition caused by hospital consolidation could all be contributors to the cost, the foundation suggests.

The high cost has multiple ripple effects. Like the pandemic, it can cause adults to delay or even forgo care. That can lead to medical complications and deteriorating conditions, adding further to the load on the physician workforce, particularly specialists. Seniors are most often putting off dental, hearing and vision care, which Medicare generally does not cover, Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) polling has found. In addition to preventing people from getting needed care, costs also kept 29% of those surveyed from taking their medications as ordered at some point in 2021.

Difficulty paying medical bills can be a source of stress that affects a family’s physical, mental and emotional health as well as their financial well-being. It also can force households to cut back on other necessities.

The most unfortunate aspect of the out-of-control U.S. health care spending, which is among the world’s highest, is that it has not brought a proportionate improvement in outcomes.

Providing better care at a reduced cost necessitates a paradigm shift on the part of patients, providers, payers and policymakers. Patients and providers must change the way they interact. With people living longer, if not necessarily healthier, they must help clinicians provide more longitudinal care. That means becoming more active in their own health, guided by their day-to-day caregivers if necessary. Information must be freely shared with all involved in a patient’s care, and providers must be attentive to social determinants and other “outside” factors.

Here, too, technology can play a key role: in gathering, sharing and analyzing clinical and claims data; in nurturing connections with patients and prompting action; in patient triage and transitions; in enabling more home-based and virtual care.

The increase in economic disparities and other social drivers

The projected physician shortage could be worse than it is. According to the AAMC, even more physicians would be needed now if marginalized minority populations (notably Blacks and Hispanics), rural residents and people lacking health insurance used health care at the same rate as those with fewer access barriers.

Of course, perpetuating barriers to care is not the way to offset a physician shortage.

As this blog has previously noted, COVID-19 exposed many long-existing disparities. Whether related to race, gender, geography, job, income or some other personal information, these disparities must be addressed. An April 2022 story in The Washington Post, for example, reported on a disparity in the types of the flu vaccines administered to senior patients, with minority patients more likely to get a standard shot instead of a costlier high-dose shot. Other race-related inequities relate to diabetes diagnoses, COVID-19 deaths, high blood pressure and life expectancy, to name a few.

Such disparities, including the social determinants of health (SDOH) that may fuel them, can no longer be disregarded. A strengthened commitment to “whole person” care, whether it occurs in a hospital or in a home or post-acute care facility, can help bridge the gaps plaguing the system.

Again, technologies that identify disparities and SDOH and connect seniors and others with social care programs can be invaluable in addressing the well-being of both individuals and populations.

Isolation and loneliness for seniors

The fact that human beings are social creatures has perhaps never been more clear than during the pandemic-related shutdowns. Grief, loneliness, isolation and their accompanying health risks — especially among seniors separated from their loved ones — were put on heartbreaking display.

This awareness reinforces the need for providers to take a holistic approach to care, and for payers and those who determine health care policy not to underestimate the influence of social factors on a person’s well-being.

While technology cannot replace face-to-face interaction, we have seen that it can help to ease the pain of separation when in-person visits are not possible. Who knows what technological advances will be available by the end of this decade to help bring people closer together?

The challenges awaiting seniors in 2030 are formidable but not invincible. Our hope, as always, lies in our resilience, our penchant for innovation and our deep-seated craving for community.

Our quest for sustainable solutions must involve a wide range of collaborators: industry workforce planners, employers, educators, inventors, policymakers and many others. We can take heart that there is strength in numbers. With more than 70 million senior Americans projected just eight years from now, it is in everyone’s best interest to find solutions that work.